Americans Flock to Areas With Harshest Climate Change Effects

Americans risk hazardous weather conditions and natural disasters in fast-growing areas, finds NerdWallet analysis.

Many, or all, of the products featured on this page are from our advertising partners who compensate us when you take certain actions on our website or click to take an action on their website. However, this does not influence our evaluations. Our opinions are our own. Here is a list of our partners and here's how we make money.

Nearly 68 million people in the U.S. were facing extreme weather alerts as of Aug. 7 — that’s about one-fifth of the U.S. population. Due to climate change, more people experience hazardous weather conditions like extreme heat, wildfires, storms and floods, and they experience them more often. Some places are more vulnerable to climate change’s impact than others, but that doesn’t stop people from moving to those spots.

A new analysis by NerdWallet finds that the majority of the fastest-growing places in the U.S. are also high-risk areas for natural hazards.

“Extreme heat and humidity is going to be a reality pretty much no matter where you move,” says Alex De Sherbinin, senior research scientist, deputy director and adjunct professor of climate at the Columbia Climate School at Columbia University in New York. “But life-threatening damages from those kinds of things are going to be more restricted to some locales than others.”

You’re more likely to experience extreme weather right now than at any other time of year. That’s because the U.S. is in its “danger season,” the period between May and October when North America experiences its worst climate impacts, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists, a nonprofit advocacy organization.

Meet MoneyNerd, your weekly news decoder

So much news. So little time. NerdWallet's new weekly newsletter makes sense of the headlines that affect your wallet.

The summer, so far, has been brutal. June was the hottest month on record for the entire planet until July broke that record, according to the Copernicus Climate Change Service, a program organized and funded by the European Union, member states and related agencies.

In the U.S., the South baked from oppressive heat; the surface water temperature off the coast of Florida reached 101 degrees Fahrenheit; and Death Valley sweltered at 128 degrees Fahrenheit — the hottest day on record. In addition, floods drowned parts of New England, and Canada’s worst-ever wildfire season is still expected to choke the northern half of the U.S with smoke periodically until the first snowfall.

These are just the immediate effects of our climate emergency. Predicted long-term effects include sea-level rise by as much as 10 to 12 inches in the 30-year period between 2020 and 2050, the same rise that was measured over a 100-year period from 1920 to 2020, according to a 2022 report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

What climate change has wrought

Climate change is exacerbating the frequency of extreme weather. The Environmental Protection Agency says climate change-induced shifting weather patterns have resulted in:

- Increasing seasonal temperatures: All of the top 10 warmest years on record worldwide have happened since 2005.

- More frequent heat waves: They occur about three times more often than they did in the 1960s

- More drought: Roughly 20% to 70% of the entire U.S. land area experienced abnormally dry conditions from 2000 to 2020. In general, certain parts of the west have experienced more drought than the rest of the country.

- More precipitation: Total annual precipitation has increased, with the notable exception of the southwest, which has seen less than usual.

- More frequent, intense, single-day precipitation events: Nine of the top 10 years for extreme one-day precipitation events have happened since 1996.

- More tropical cyclone activity: It has increased over the last 20 years, impacting the Gulf of Mexico, the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean.

- Large floods: They have become more frequent throughout the Northeast, Pacific Northwest and parts of the northern Great Plains.

The United Nations lists a host of frightening side effects of climate change related to the ones above that include food scarcity, species extinction, health risks, poverty and displacement.

Fast-growing places are at high risk for worsening climate conditions

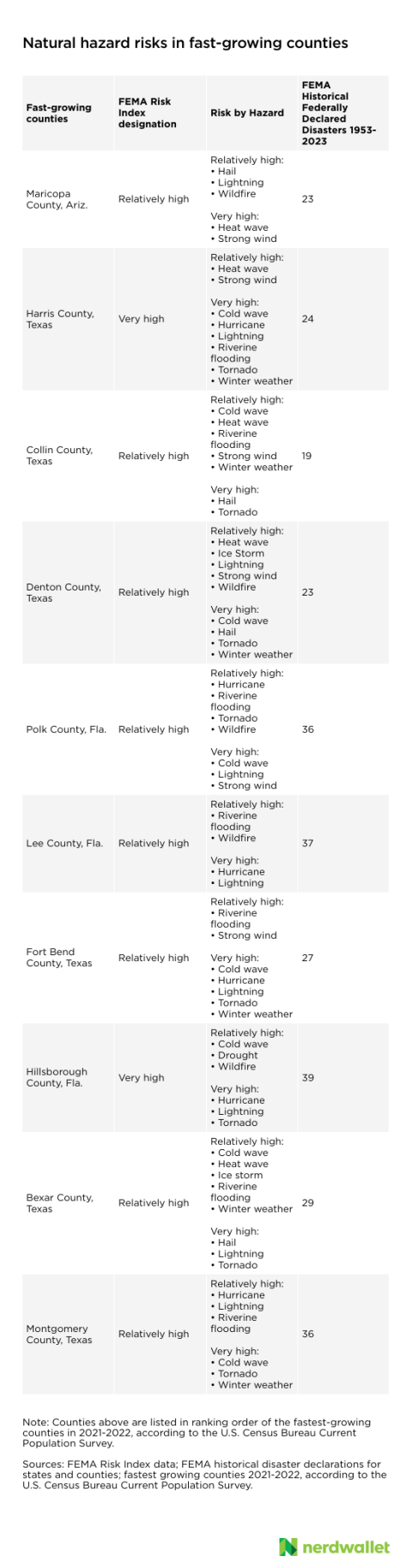

Among the 10 fastest-growing counties, two are considered at very high risk for natural hazards and eight are considered at relatively high risk for natural hazards. None of the fastest-growing counties are considered at relatively moderate risk or low risk.

For context, of the 3,231 counties the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) risk index covers, 15 are considered at very high risk (0.46%); 129 are considered at relatively high risk (3.99%); and 397 are considered at relatively moderate risk (12.29%).

All of the fastest-growing counties are located in the western or southern parts of the U.S., including six counties in Texas, three in Florida and one in Arizona.

Each of the counties carries its own potential hazards: hurricanes in all three counties in Florida; heat waves in Maricopa County, Arizona; and a near-biblical assortment of risks in the Texas counties, including cold waves, heat waves, hurricanes, tornadoes, wildfires and more.

There have been 4,762 federally declared disasters in the U.S. since 1953, according to FEMA data. Each of the fastest-growing counties has had its fair share of federally declared disasters in the last 70 years. Hillsborough County, Florida, had the most events (39), followed closely by Lee County, Florida (37), and Montgomery County, Texas (36). In each of these counties, tropical storms were the cause of the disasters.

Warming sea surface temperatures due to climate change cause hurricanes that are larger, have more intense wind speeds and greater precipitation, according to the Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, an environmental policy think tank.

What are the risks in the fast-growing county?

The No. 1 fastest-growing county for 2021-2022 is Maricopa County, Arizona, which includes the city of Phoenix. Maricopa County has seen a 19% increase in its population since 2010. As of 2022, its population is an estimated 4.5 million. Maricopa County is particularly vulnerable to heat, dry conditions and resulting drought. Ironically, due to dry conditions, the land is also vulnerable to flooding: Among the 23 federally declared disasters Maricopa has experienced since 1953, nine were floods.

After assessing groundwater conditions in the Phoenix metropolitan area, the Arizona Department of Water Resources projects that about 4% of the region’s demand for groundwater will not be met over a period of 100 years, unless further action is taken. But while groundwater isn’t technically a nonrenewable resource, it's not easily renewable either, and groundwater supplies are becoming scarce in some areas of the country, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Increasing population puts stress on natural resources like water, levels of which are more difficult to maintain during times of extreme heat. The Arizona state government recently put limits on new housing construction in the Phoenix area due to the dwindling supply of groundwater.

What are the risks in “very high risk” counties?

Two of the fastest-growing counties in the U.S. are considered “very high risk” for natural hazards: Harris County, Texas, and Hillsborough County, Florida.

- Harris County, Texas: It's the most populous county in all of Texas, with 4.7 million people, and includes the city of Houston, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Since 2010 it has seen a 16.8% increase in its population. Harris County is at very high risk for extreme weather conditions including cold waves, lightning and winter weather, as well as natural disasters such as riverine flooding and tornadoes. Harris County has had 24 federally declared disasters, including 11 tropical storms, since 1953.

- Hillsborough County, Florida: It’s located in the west-central part of Florida and includes the city of Tampa. Hillsborough County has a population of 1.5 million people. Since 2010, it has seen a 23% increase in its population. It has a relatively high risk for cold waves, drought and wildfires, and very high risk of hurricanes, lightning and tornadoes. More hurricanes hit Florida than any other place in the U.S., according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Hillsborough County has had 39 federally declared disasters, including 18 tropical storms, since 1953.

What happens when you move to a high-risk area

In general, moving from one place to another is heavily age-dependent, says De Sherbinin. Younger people tend to be more mobile as they establish their careers, and tend to settle down when they have a family. Older people migrate at the end of their careers because they want to retire somewhere near family or have amenities they value most.

“These classical motivations have been relatively impervious to the sense that there is a growing risk that we face as a society,” says De Sherbinin.

Prioritizing your lifestyle and career preferences over avoiding extreme ecological risks is simply human nature, says De Sherbinin. Why? People don’t necessarily think catastrophe will happen to them.

De Sherbinin says when you move to an area that’s highly vulnerable to climate change effects, the rationalization usually goes something like this: “‘I’m not going to be the one to lose my house over the cliff into the Pacific Ocean, because I’m just lucky.’”

The U.S. tends to be an outlier when it comes to people moving into areas where risks are really high, says De Sherbinin, who studies the human aspects of global environmental change. But the higher the risk of natural hazards, the more vulnerable the population is to direct and secondary impacts of weather events. Direct impacts are more immediate bodily harm and property harm, while secondary impacts are typically longer-term, such as economic loss, social unrest and potentially a retreat from the area.

As stated earlier, climate change is worsening the likelihood and the extreme nature of weather events, which means those high risks may manifest in a real way and more often.

For example, the extreme heat conditions in Texas recently were made significantly more likely by climate change, according to the U.S. Climate Shift Index (CSI) Map. Intense heat in Houston, the county seat for Harris County — the second fastest-growing county according to the Census Bureau — is now five times more common due to climate change, according to the CSI Map. Without climate change, extreme heat would otherwise be rare for that area, according to the CSI scale.

About 80% of the U.S. population lives in cities where “heat island” effects exacerbate extreme heat conditions. Among the 44 major cities analyzed by Climate Central, a nonprofit science and news organization, nine have more than 1 million people who feel at least 8 degrees Fahrenheit hotter due to the urban environment. Among those nine cities, three are in the fastest-growing counties listed in this analysis. Houston is on the list, as well as Phoenix in Maricopa County, Arizona, and San Antonio in Bexar County, Texas.

What it means to live in an area at high risk for climate change

Very few places are immune to worsening climate conditions. Those who live in or move to an area at high risk for natural hazards may contend with a host of expenses, including:

- Higher risk to homes, vehicles or, even livelihoods.

- Higher costs to insure properties or businesses.

- Higher energy costs to heat and/or cool homes and businesses.

- Higher emergency fund needs.

- Risk-mitigating costs such as purchasing a generator, elevating structures, creating defensible space or other home alterations to fortify structures.

Weather-battered places may become uninsurable

Moving to an area that’s at high risk for natural hazards may cost you more than you bargained for, in more ways than one, beginning with property insurance.

Insurance giants State Farm and Allstate recently announced that they’re no longer issuing new homeowner policies in California. State Farm cites “rapidly growing catastrophe exposure” among its reasons for pulling back.

Loretta Worters, vice president of media relations for the Insurance Information Institute, says the industry is at a pivotal point as a whole. Insurers are developing strategies to better understand the risks of extreme weather events, but it’s getting more difficult to price risk, she says. It also costs consumers more to get insurance because the risks are so great, Worters says.

“Everybody wants this idyllic kind of lifestyle; we want to be on the coast or we want to be in these beautiful, serene areas where there's lots of shrubbery and privacy,” says Worters. “But you can't get fire trucks in — into areas that are prone to wildfires. A lot of these people’s homes are situated such that it's hard for the trucks to get up there because they're on winding roads.”

California isn’t the only state where insurance may be hard to come by due to chronic weather events. Flood-prone states have long felt the sting of rising rates and difficulty getting coverage. A recently rolled-out change to the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is making it even more expensive. The program is often the only one available in flood-prone areas.

FEMA says the rate increases, known as “Risk Rating 2.0,” will enable the agency to distribute premiums and set rates that are more equitable than in the past. The new methodology assesses more variables than it used to like flood frequency, types of flooding, the property’s distance to a water source as well as its elevation, and costs to rebuild.

On June 1, a group of 10 states joined a suit led by Louisiana Attorney Gen. Jeff Landry against FEMA, the Department of Homeland Security and the Federal Insurance and Mitigation Administration in an attempt to block steep rate increases to the NFIP that went fully into effect on April 1. The states — which include Florida, Idaho, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, North Dakota, South Carolina, Texas and Virginia — argue the higher rates could force policyholders to drop their coverage or end up surrendering their homes and businesses.

Insurance costs have climbed in the last few decades: Insured catastrophe losses have increased by nearly 700% since the 1980s when adjusted for inflation, according to the Insurance Information Institute. And in 2021, insured losses from natural catastrophes totaled $130 billion — 76% higher than the 21st-century average.

If more insurers pull out of areas due to chronic weather conditions like wildfires and hurricanes, areas could become astronomically expensive to insure, if not altogether uninsurable. Fewer private insurers available means homeowners will likely need to turn to Fair Access to Insurance Requirements (FAIR) plans. All states have some type of a plan, which is instituted at the state level and backed by private insurers licensed to write insurance in the state. All of the companies have a proportionate share in any profits, losses and expenses of the plans.

FAIR plans usually offer only basic coverage and are used “as a last resort,” according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), a nonprofit regulatory support organization.

Worters, of the Insurance Information Institute, says FAIR plans are likely to have higher deductibles and less coverage, and they may be more difficult to obtain. Still, they’re widely used: 10% of Florida homeowners have insurance through the state’s FAIR plan, the Citizens Property Insurance Corp., as of March 2022, according to the NAIC.

Rising rates are a source of anxiety and frustration for policyholders, says Worters, but she adds that the insurance industry isn’t the only party that must respond to worsening climate conditions. Property risks can be mitigated, she says, through policy and property safeguards such as building codes in hurricane-prone areas or defensible space requirements — buffers around property — in wildfire-prone areas.

“We’re insuring it, but if you continue to live in these areas and you don’t take any measures to safeguard your home or your business, it just makes things worse.”

Stephanie Pincetl, founding director and professor at the California Center for Sustainable Communities at UCLA, says changing how we live will be crucial to combating the impacts of climate change. “I think that we need to realize the American pattern of land use contributes 100% towards climate change and also has lots and lots of other ramifications. And we have not been dealing with that,” says Pincetl. “We have large houses, we have many bathrooms, we have private gardens and so on. And those are inherently energy-intensive, land-intensive and water-intensive.”

Will people migrate due to climate change?

If climate conditions worsen in your area, you’ll inevitably be faced with this conundrum: Should I stay, or should I go?

The answer to that question will largely depend on if you’re responding to an ongoing climate issue or you’re forced to respond to an event, says Andrew Jakabovics, vice president for policy development at Enterprise Community Partners and co-author of “Housing Markets and Climate Migration,” by the Urban Institute, an economic and social policy think tank.

The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), an independent think tank, says climate change-fueled disasters are increasing migration worldwide. CFR finds most migration occurs within national borders, but cross-border migration is expected to rise. At the end of 2022, 8.7 million people worldwide — 675,000 in the U.S. alone — were living in internal displacement due to weather-related disasters, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre (IDMC). From 2008 to 2022, 11.1 million people were displaced in the U.S. due to weather-related disasters, the IDMC found.

Chronically worsening conditions — annual wildfires, hurricanes, heat waves and floods — may not necessarily destroy your property, but they’re certainly going to impact your life. Experts say extreme weather events are the ones that make it more difficult to stand your ground.

“We’re not well-evolved in terms of our reasoning to kind of take into account low-probability but very high-impact events,” says De Sherbinin. “We can react when something massive happens and decide, ‘Oh, God, that was really way too much,’ but we're not well-evolved to address things that are kind of gradually changing over time.”

And for people who already live in high-risk areas, their single biggest investment is their home, says De Sherbinin. And they’re not going to leave just “because flood risk has risen from one in 100 years to one in 10 years,” he says. “They just roll the dice and figure that out later. Or they’ll lobby to get their government to build the necessary infrastructure to protect them.”

When people do leave, they rarely go far. The Conversation, a nonprofit news organization largely written by academics and researchers, mapped out where people move following flooding disasters through FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program from 1990 to 2017. It’s a buyout program that pays homeowners to purchase and demolish flood-damaged homes. The data shows that no matter where the flooding occurred, most homeowners who took a buyout stayed close by — just 7.4 miles was the median distance. Three in four people stayed within 20 miles of their original homes.

Among those who do leave, typically familial ties and communal ties drive relocation choices, says Jakabovics. “If you're leaving the island of Puerto Rico, there was a kind of a preexisting population in parts of Florida. That was by no means the only geography that people moved to, but there was a concentration there,” says Jakabovics.

There are also people who, even in the event of a disaster, want to return to their homes because, understandably, it’s their home. At that point, habitability becomes a question of safety compliance, insurance and more. If you’re not a homeowner and you want to go back, you may face an even bigger challenge.

“If you're a renter, right, you have very little control over the physical state of the property. And so, it depends on what the landlord has to or can do,” says Jakabovics. “We know that post-Hurricane Katrina, a lot of the rental stock was uninhabitable and some of the new insurance requirements and things like that made it very, very difficult to keep those properties habitable.”

Of course, the longer you wait to leave a high-risk area, the more challenging it might be. “Instead of a kind of orderly, thoughtful process, which Americans have a very hard time with, people will be losing their shirts,” says Pincetl.“They won't be able to sell their properties.”

Is anywhere really safe to live?

Nowhere is entirely safe to live, but some areas will be less prone to certain disasters than others. Heat is most extreme in the southern states, and especially in the most arid locations; flooding is worse along the coasts and near large bodies of water; and tornadoes are more common in the Great Plains. The San Andreas fault stretches along the entire California coast, while other, smaller fault lines are spread throughout the west. The highest-threat volcanoes sit along the West Coast of the continental U.S., as well as Alaska and Hawaii. No place is immune.

Whether you can go somewhere “safer” will depend on your financial situation. For millions of Americans who live in poverty, the more relevant question is likely to be, “Can I afford to go?”

Populations that are more often affected by and less able to withstand the health impacts of climate change include older adults, children, low-income communities and some communities of color, according to a 2018 government report known as the “Fourth National Climate Assessment.”

Leaving one area for another will always be easier for those with the financial resources to do so. When extreme weather or a natural disaster hits, those with greater socioeconomic challenges have less ability to leave. And they’ll also bear the brunt of worsening weather conditions to come.

METHODOLOGY

NerdWallet drew the list of fastest-growing counties using 2021-2022 data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the most recent available data set. The fastest-growing counties in this list were limited to the top 10. The fastest-growing counties are those with the highest numeric population increases over a set period. The 10 counties were then matched with their corresponding risks using the Federal Emergency Management Agency National Risk Index and FEMA’s historical data for disaster declarations from 1953 onward.

(Lead photo by Mario Tama/Getty Images News via Getty Image)

Article sources

NerdWallet writers are subject matter authorities who use primary,

trustworthy sources to inform their work, including peer-reviewed

studies, government websites, academic research and interviews with

industry experts. All content is fact-checked for accuracy, timeliness

and relevance. You can learn more about NerdWallet's high

standards for journalism by reading our

editorial guidelines.

Related articles