UAW Worker: ‘These Jobs Were Gold Standard’

The union is on strike at targeted locations across the Big Three auto companies.

Many, or all, of the products featured on this page are from our advertising partners who compensate us when you take certain actions on our website or click to take an action on their website. However, this does not influence our evaluations. Our opinions are our own. Here is a list of our partners and here's how we make money.

For updates on the UAW strike, see our list of who is on strike today in the U.S.

United Auto Workers is officially on strike. Negotiations failed this week between the union and the Big Three auto companies — Ford, General Motors and Stellantis (a multinational conglomerate that includes Chrysler).

The strikes started in three locations:

- Ford: Michigan Assembly Plant in Wayne, Mich.

- Stellantis: Toledo Assembly Complex in Toledo, Ohio

- GM: Wentzville Assembly Plant in Wentzville, Mo.

Other plants may follow at any time. It’s a strategy that UAW President Shawn Fain calls a “Stand-Up Strike,” he said during a Facebook Live stream on Sept. 13.

Meet MoneyNerd, your weekly news decoder

So much news. So little time. NerdWallet's new weekly newsletter makes sense of the headlines that affect your wallet.

Each of the Big Three has proposed pay raises nowhere near what UAW is aiming for. Fain said the companies are also unwilling to bend to UAW’s request for increased pension and retiree health care.

The UAW represents nearly 150,000 workers. The union joins other major strikes sweeping the U.S., including Hollywood actors with SAG-AFTRA and film and TV writers with the WGA.

To get a personal perspective on the UAW strike, NerdWallet spoke with Nick Livick, a third-generation UAW member who works at General Motors’ Fairfax Assembly & Stamping in Kansas City, Kansas. He has worked at the plant since 2012 and is a pool worker, which means he is expected to walk onto any job and learn it quickly. We spoke about why U.S. auto manufacturing workers are demanding improved working conditions, higher pay and better benefits.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

NerdWallet: You're a third-generation UAW member. Can you share some of your family's background with the union?

Nick Livick: My grandfather started at the [American Motors Corp.] in Kenosha, Wisconsin, in the early '60s. After that plant closed, he got hired at General Motors in Janesville, Wisconsin. He was able to move his family because of the wage that the UAW had negotiated.

My mother got hired in 1996. I was still young and I can remember this moment when things started changing. You weren’t using so many hand-me-downs; you got to buy your own set of clothes. You weren’t using a notebook from last year; you got new school supplies.

When I got hired as a temp, my wage started out at $15. More than a decade after I got hired the starting wage hasn’t changed much. It was a lot easier in 2012 to make that wage and live.

“ I know if we go out on strike, I'm going to lose money. But I never think about it like that because it's about the worker that's coming in after me so that they can have a better shot at their working life than I got. ”

Nick Livick, third-generation UAW worker in Kansas City, Kansas.

These jobs were gold standard jobs, but then during the Great Recession, when Janesville closed, we were forced to take a lot of concessions from the government-mandated bailout. And we were promised that we’d get these back as soon as we got profitable again. We gave up a lot and we did it because we wanted these companies to succeed. There’s a lot of pride in where we work and we put a lot of pride into the work to make sure it’s a quality vehicle. But those benefits never came back. There’s no retiree health care, no pensions, we get less sub pay and we get even less vacation time.

NerdWallet: Can you explain more about why the UAW is striking?

Nick Livick: At the end of the day, it comes down to simple respect. A lot of the benefits that we're currently fighting for we already had and we gave up for the company to save them from their mismanagement.

They have temps that work up to two years before they get hired full time. During the pandemic, you saw temps that were getting close to their two years, then all of a sudden none of us were working. When layoffs happened, temps started the clock over.

There’s an eight-year earning scale even after you’ve been a temp for up to two years. So you’re talking about a third of your working career where they’re expecting you to save for your own retirement. It’s just impossible.

You also have the tiered work system where I could be working next to somebody doing the same job who is not getting the same pay or the same benefits. Conditions are just getting worse.

They can hardly find anyone to come in to work because starting wages are only $16.67. You can go down to my local QuikTrip and get paid $19 an hour. Who’s going to do a rough, tough job like assembly work when they could be working somewhere else for more money? Long-term benefits are what ties people to the plant.

Then, you look at the work schedule. At Stellantis, they went on a 90-day critical status leading up to contract negotiations where they’re forced to work 90 days straight. You’re working seven days a week, 12-hour shifts and can only take one day off a month. It’s just insane.

There are days when I wake up where both of my hands are numb because of the work and I just can't feel them. And there's nothing I can do other than stretch it out or shake them. When you’re working insane hours, you have no time to recover.

These jobs are tough. You’re lucky if your facility is climate-controlled, but even then, it’s not true air conditioning so it’s still going to be 80 or 90 degrees in the plant. And if you’re not climate-controlled then if it’s 110 outside, it’s going to be hotter than 110 in the factory.

“ We need these benefits for when we retire because our bodies are going to be broken. ”

Nick Livick, third-generation UAW worker in Kansas City, Kansas.

We're fighting to get back to a basic standard of living. And not only that, but to save these jobs for the next generation. I know if we go out on strike, I'm going to lose money. But I never think about it like that because it's about the worker that's coming in after me so that they can have a better shot at their working life than I got.

NerdWallet: Tell me about some of the demands that the UAW is making.

Nick Livick: We want to end the payment tiers. Like I said, you got people working for different wages, different benefits right next to each other. It's a way that management uses to divide workers. I mean, ‘equal pay for equal work’ — I think any worker can really latch on to that and agree with it.

Retirees haven't gotten an increase in over a decade. They’re being killed by inflation. We need to get cost-of-living adjustments — COLA — back because we've seen what happens as inflation erodes wages. It's not uncommon for an auto worker to have knee surgeries, elbow surgery, hand surgery, wrist surgery, back surgery. We need these benefits for when we retire because our bodies are going to be broken.

It’s incredibly physically demanding work and it never stops. At an office, you know, you can kind of get up and stretch your legs, walk around, go to the bathroom, stop and talk to someone if you're feeling a little bit even mentally exhausted. But on the assembly line, it never stops coming. You've always got to do the next job.

There’s one demand that’s a little bit more 'audacious,' as Shawn [Fain] says, and it’s the 32-hour workweek for 40 hours of pay. It comes from the sheer amount of insane hours that we’re working. As we transition to [electric vehicles], it's going to take less manpower. With all this increased productivity, workers should be allowed to experience their lives outside of work. Right now, if you're working 90 days in a row, seven days a week and 12-hour days, you have no standard of living.

NerdWallet: Is there anything else that you think is important for people to understand about this strike?

Nick Livick: That we are fighting for more than just us. It's about the economic system in this country. Everything that organized labor wins reverberates through the entire economy. So it's not just our fight. It's everybody's fight.

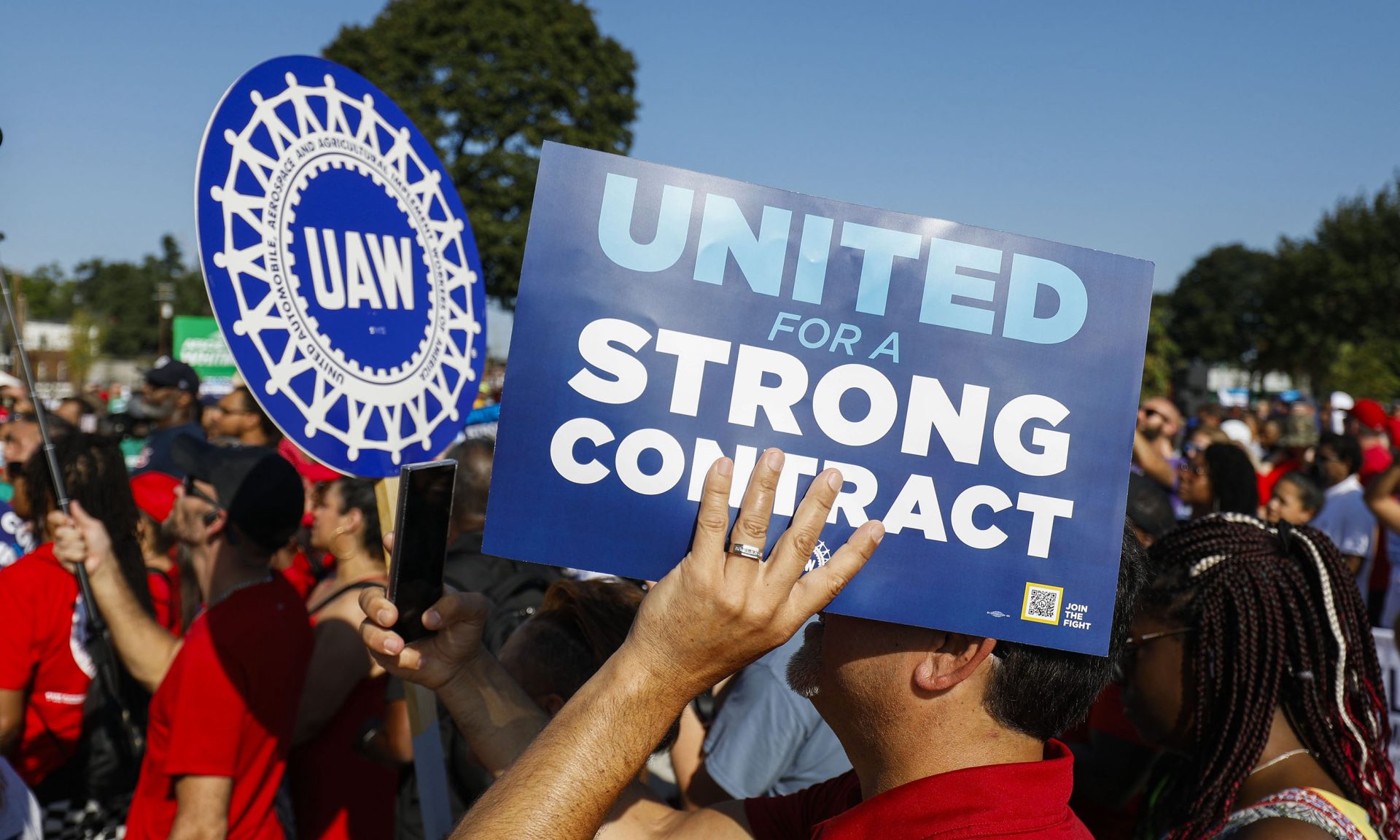

(Photo of Detroit Labor Day Parade on Sept. 4, 2023, by Bill Pugliano/Getty News Images via Getty Images)

Article sources

NerdWallet writers are subject matter authorities who use primary,

trustworthy sources to inform their work, including peer-reviewed

studies, government websites, academic research and interviews with

industry experts. All content is fact-checked for accuracy, timeliness

and relevance. You can learn more about NerdWallet's high

standards for journalism by reading our

editorial guidelines.

Related articles