What Happens If the U.S. Can’t Pay Its Bills? ‘Catastrophe’

A default on U.S. debt could trigger a worldwide recession and upend stock markets in addition to wreaking havoc in Americans' financial lives.

Many, or all, of the products featured on this page are from our advertising partners who compensate us when you take certain actions on our website or click to take an action on their website. However, this does not influence our evaluations. Our opinions are our own. Here is a list of our partners and here's how we make money.

A few short weeks are left for Congress — or, perhaps, President Joe Biden — to take action and lift the debt ceiling before tick, tick, tick … boom goes the economy.

The so-called “X-date” — when the federal government can no longer meet its legal obligations — could be as early as June 1, according to a May 1 letter from U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to Congress. Yellen reiterated the same sentiments in another letter to Congress on May 15.

“If Congress fails to increase the debt limit, it would cause severe hardship to American families, harm our global leadership position, and raise questions about our ability to defend our national security interests,” Yellen wrote in the most recent letter. She warned of "catastrophe" in a May 11 news conference.

The Congressional Budget Office released its own projections on May 12, which left more wiggle room: somewhere in the first two weeks of June. The report also said the U.S. Treasury’s cash and extraordinary measures would be sufficient to fund the government until June 15.

While negotiations between the parties continue, we all wait to see if the federal government runs out of money to pay its bills and defaults. What comes next isn’t pretty.

A range of problems

If the default lasts for weeks or more, rather than days, it could trigger a fire-and-brimstone, Armageddon-level financial crisis for the U.S. and global economies.

A report from the White House Council of Economic Advisors in October 2021 warned of the possible effects of the U.S. defaulting, which include a worldwide recession, worldwide frozen credit markets, plunging stock markets and mass worldwide layoffs. The real gross domestic product, or GDP, could also fall to levels not seen since the Great Recession.

The U.S. has defaulted only once, in 1979, and it was an unintentional snafu — the result of a technical check-processing glitch that delayed payments to certain U.S. Treasury bondholders. The whole affair affected a few investors and was remedied within weeks.

But the 1979 default was not intentional. And from the point of view of the global markets, there's a world of difference between a short-lived administrative snag and a full-blown default as a result of Congress failing to raise the debt limit.

Meet MoneyNerd, your weekly news decoder

So much news. So little time. NerdWallet's new weekly newsletter makes sense of the headlines that affect your wallet.

A default could happen in two stages. First, payments to Social Security recipients and federal employees might be delayed. Next, the federal government would be unable to service its debt or pay interest to its bondholders. U.S. debt is sold as bonds and securities to private investors, corporations or other governments. Just the threat of default would cause market upheaval: A big drop in demand for U.S. debt as its credit rating is downgraded and sold, followed by a spike in interest rates. The U.S. would need to promise higher interest payments to justify the increased risk of buying and holding its debt.

Here’s what else you can expect if the U.S. defaults on its debt.

A sell-off of U.S. debt

A default could provoke a sell-off in debt issued by the U.S., considered among the safest and most stable securities in the world. Such a sell-off of U.S. Treasurys would have far-reaching repercussions.

Money market funds could see volatility

Money market funds are low-risk, liquid mutual funds that invest in short-term, high-credit quality debt, such as U.S. Treasury bills. Conservative investors use these funds as they typically shield against volatility and are less susceptible to changes in interest rates.

However, in the past, money market funds made up of U.S. Treasurys have seen increased volatility when the U.S. ran up against debt ceiling limits and signaled potential government default. Yields on shorter-term T-bills go up because they are impacted more compared with longer-term bonds, which gives investors more time for markets to calm down.

(Note that money market funds aren't the same as money market deposit accounts, which are a type of federally insured savings account offered by financial institutions.)

Federal benefits would be suspended

In the event of a default, federal benefits would be delayed or suspended entirely. Those include: Social Security; Medicare and Medicaid; Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP, benefits; housing assistance; and assistance for veterans.

Although a default wouldn’t affect Medicare and Medicaid recipients directly, delays in payments to providers could make them reluctant to treat Medicare and Medicaid patients.

Stock markets would roil

A default would likely trigger a downgrade of the U.S. credit rating — the S&P downgraded the nation’s credit rating only once before, in 2011, after a last-minute debt ceiling deal was reached. A credit downgrade happens when an international credit rating agency, like Standard & Poor’s, determines the country’s risk of defaulting on sovereign bonds has increased relative to other peer nations or an average, said Andrew Hanson, assistant professor of economics at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, via email.

A default combined with the downgraded credit rating would in turn cause the markets to tank, the White House’s Council of Economic Advisors said in 2021.

If current debt ceiling talks continue for too long, the markets are likely to become more volatile. When markets are volatile, there is a risk of a run on banks — where deposit customers withdraw money because of fear their bank could collapse — in an already uncertain banking environment. If an institution isn’t able to meet the increased need for withdrawals, it could fail.

Interest rates would increase for loans

As debt ceiling negotiations linger, Americans could see rates increase on established lending products with variable loans, including personal and small-business lines of credit, credit cards and certain student loans. Issuers may also decrease existing credit lines.

Credit lenders may have less capital to lend or may tighten their standards, which would make it more difficult to get new credit.

Depending on the timing of a default and how long the effects are felt, rates could increase on new fixed auto loans, federal or private student loans and personal or small-business loans.

Credit card rates could rise

Americans could see rates increase on credit cards beyond what they’ve seen since the Fed began hiking rates in 2022. Credit cards already have higher interest rates than many other loans, so carrying a balance during these economic times is more expensive. Those with debt who are in a position to pay it off should start making moves to do so.

It’s also not uncommon for lenders to cut credit limits, close accounts or require higher credit scores for approval when the economy is in distress. Lenders took these actions during the Great Recession and early in the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a 2022 report by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

Mortgage rates would likely increase

The real estate website Zillow projects that following the U.S. defaulting on its debts, mortgage rates could rise as much as two percentage points by September before declining. With that, we’d see a massive contraction of the housing market.

A debt ceiling crisis won’t impact those with fixed-rate mortgages or fixed-rate home equity loans. But adjustable-rate mortgage, or ARM, holders may feel these rising rates. Those in the fixed period of their ARM could see rates rise when reaching their first adjustment. Anyone struggling to keep up with payments is encouraged to reach out to their lender early to discuss their options. A HUD-certified housing counselor can help homeowners explore alternatives to delinquency and foreclosure.

If the prime rate (the baseline rate that lenders use to set interest rates for lines of credit) increases, borrowers with variable-rate home equity lines of credit, or HELOCs, will also see their rate climb.

Tax refunds could be delayed

If the debt ceiling isn’t raised, it could take more time for tax filers to receive their refunds — which usually come within 21 days of e-filing. If the government defaults, those who file late run a risk of a delayed refund.

A more immediate concern: A potential credit downgrade

Even the threat of a default can lead to a downgrade of the U.S. credit rating, but it won’t necessarily happen.

“Given the Treasury and FOMC’s commitment to honoring extant Treasurys, the chance of a U.S. credit downgrade has historically been very slim,” Hanson said.

Even if default is avoided, the uncertainty created by brinkmanship on the debt limit has “serious economic costs,” Yellen warned at a press conference in Japan on May 11.

“We could see a rise in interest rates drive up payments on mortgages, auto loans and credit cards,” Yellen said. “We are already seeing spikes in interest rates for debt due around the date that the debt limit may bind.”

Hanson said a default could make it more difficult to finance future spending with debt since fewer people would be willing to hold U.S. Treasurys rather than other sovereign bonds that have a higher credit rating. And also because yields on Treasury bonds would increase in an effort to incentivize investors to buy, at a cost to the Treasury.

NerdWallet writers Kate Ashford, Margarette Burnette, Taylor Getler, Jaime Hanson, Craig Joseph, Melissa Lambarena and Kurt Woock contributed to this article.

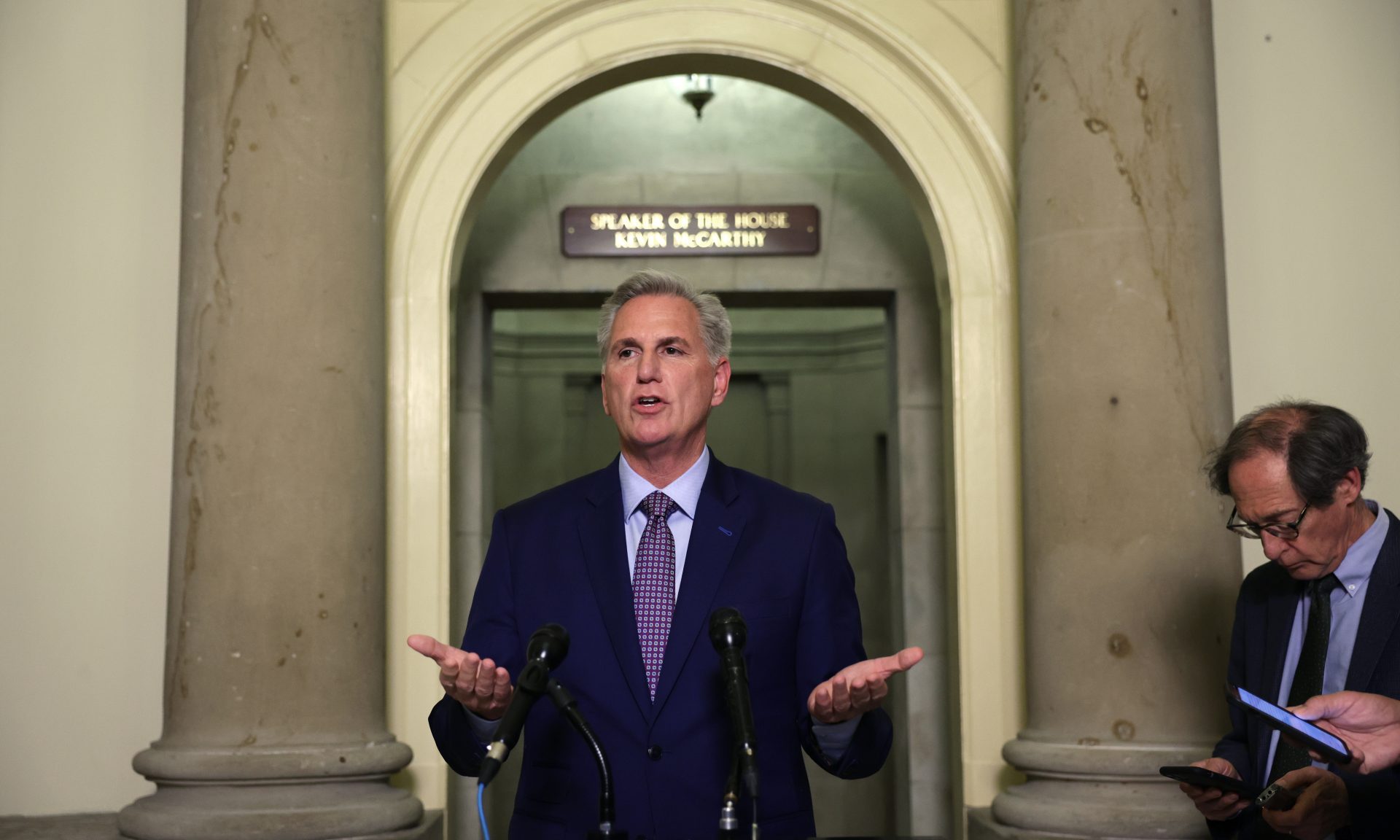

(Photo by Alex Wong/Getty Images)

Article sources

NerdWallet writers are subject matter authorities who use primary,

trustworthy sources to inform their work, including peer-reviewed

studies, government websites, academic research and interviews with

industry experts. All content is fact-checked for accuracy, timeliness

and relevance. You can learn more about NerdWallet's high

standards for journalism by reading our

editorial guidelines.

Related articles