What Is a Tariff?

The government might impose a tax on imported goods to raise revenue or protect domestic industries.

Many, or all, of the products featured on this page are from our advertising partners who compensate us when you take certain actions on our website or click to take an action on their website. However, this does not influence our evaluations. Our opinions are our own. Here is a list of our partners and here's how we make money.

A tariff is a tax levied on imported goods when they enter the country. It could be calculated as a fixed amount or a percentage of the price of the goods it’s applied to. The government might impose a tariff to raise revenue or protect domestic interests. Whatever the purpose of the tariff, economists say much of its cost is passed through to domestic producers and consumers in the form of higher prices.

President Donald Trump has implemented a wide variety of tariffs in his second term.

» See the latest tariff news.

Who has the power to impose tariffs?

Generally, decisions about taxes fall to Congress. But, through a string of laws dating back to 1934, legislators have given the president and his cabinet considerable authority over tariffs.

Most recently, President Donald Trump used his authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977 (IEEPA) to enact wide-ranging tariffs on nearly all U.S. trade partners.

- On April 2, he announced a 10% tariff on imports from all countries, as well as higher “reciprocal” tariffs targeting countries with the largest trade deficits with the U.S. He justified the move by saying, “foreign trade and economic practices have created a national emergency,” according to an April 2 press release.

- Prior to that, Trump used the same authority to levy tariffs on Canada, China and Mexico. In that instance, he said trafficking of drugs like fentanyl across U.S. borders poses a national security threat.

His authority to use the IEEPA to impose tariffs has been challenged and the Supreme Court is expected to rule on the case early in 2026.

Trump also has levied tariffs on steel and aluminum imports — now and during his first term in 2018 — citing part of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, which allows the president to set tariffs on imports that the secretary of commerce says pose a threat to national security .

President Joe Biden did something similar in May 2024, citing a section of the Trade Act of 1974 to empower the Office of the United State Trade Representative to increase tariffs on China.

Meet MoneyNerd, your weekly news decoder

So much news. So little time. NerdWallet's new weekly newsletter makes sense of the headlines that affect your wallet.

Critics of these uses of tariffs, including members of Congress, have attempted to limit the president’s unilateral tariff-setting power. In a recent example, attorneys general in 12 states filed a lawsuit seeking to block sweeping tariffs enacted by Trump. The suit claims that the president doesn’t have authority to impose tariffs under the IEEPA .

Who pays tariffs?

Tariffs imposed by the U.S. government are paid by the domestic companies that import the relevant goods or materials. Importers can handle that in a number of ways, including:

- Negotiating for the exporter to reduce its price, offsetting all or some of the cost of the tariff.

- Absorbing all or part of the higher import costs themselves by cutting their profit margin.

- Passing on all or part of the cost to customers by raising prices.

Some U.S. companies that depend on imported goods and materials already have outlined plans to raise prices to pay for tariff increases promised by Trump during his presidential campaign, the Washington Post reported ahead of Trump’s election win .

Because the tax is levied on import prices, not consumer prices, the price hike that consumers face shouldn’t be as big as the one paid by the importer, Paul Donovan, chief economist with UBS Global Wealth Management, said in commentary released Oct. 16 .

The import price typically represents less than half of the consumer price of a good, Donovan said. That means, “a 20% tariff should raise consumer prices for imported goods less than 10%.”

That’s no guarantee, though. Donovan added: “Retailers may use the narrative of a 20% tax to raise their prices more than the tariff cost alone.”

What's the purpose of a tariff?

A nation like the United States might impose tariffs to increase revenues for the federal government, motivate trade partners to change behavior or protect domestic industries that are losing to foreign competitors.

Generate revenue

For a long time, import tariffs were the U.S. government’s main source of income, according to the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank. But that started to change when the first income tax was put in place during the Civil War in 1862 .

In fact, tariffs haven’t been a major part of the U.S. budget since 1914, according to economic researchers at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, a nonpartisan think tank .

For tariffs to be a reliable income source, they have to be low and targeted enough to continue encouraging trade, the Cato Institute says. If they’re too high or broad, the market will shift to favor goods from sources that aren't taxed in the same way — or discourage imports altogether.

That can put this goal of generating revenue at odds with the other goals of import tariffs.

Influence trade partners

Especially recently, it’s common for U.S. tariffs to serve as a foreign relations tool to influence trade partners’ behavior. By taxing certain goods — perhaps those coming from a particular country or region — the U.S. is trying to shift the market away from those sources.

Protect domestic industries

At the same time that tariffs could penalize a trade partner, they can buoy domestic industry by creating demand for goods from an alternative source. The goal is to protect domestic producers from cheaper goods being made by foreign competitors. In turn, that’s meant to create jobs and promote innovation at U.S.-based companies.

Encouraging domestic production of certain goods also is believed to serve a national security interest.

Are tariffs good or bad?

Mainstream economists largely characterize tariffs as inefficient and ineffective, especially when imposed broadly.

Here are a couple examples of economists casting doubt on the use of tariffs:

In an October 2024 article, Kimberly Clausing and Maurice Obstfeld of the Peterson Institute for International Economics said across-the-board tariffs, like those proposed by Trump, are costly because they raise prices not only on imported goods but also on those sourced domestically .

“Simply put, protectionism reduces the gains from trade,” Clausing and Obstfeld said. “We choose to pay more than necessary for some goods (imports and their domestic substitutes) instead of focusing on those goods that we produce more efficiently than foreigners.”

In another recent article — this one written by Michael Strain, director of economic policy studies and senior fellow with the American Enterprise Institute — argued that trade policies of the past two administrations have not met their own goals .

“They have caused manufacturing employment to decline, not to increase,” Strain wrote. “They have not reduced the overall trade deficit; they have not led to a substantial decoupling of the U.S. and Chinese economies.”

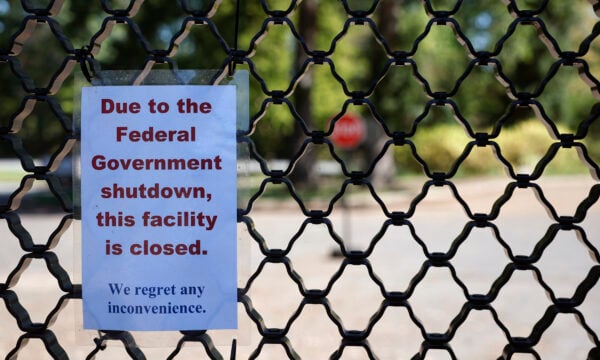

Photo by Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Article sources

NerdWallet writers are subject matter authorities who use primary,

trustworthy sources to inform their work, including peer-reviewed

studies, government websites, academic research and interviews with

industry experts. All content is fact-checked for accuracy, timeliness

and relevance. You can learn more about NerdWallet's high

standards for journalism by reading our

editorial guidelines.

- 1. U.S. Department of Commerce. Section 232 investigation on the effect of imports of steel on U.S. national security.

- 2. Office of the New York State Attorney General. Attorney General James and Governor Hochul Announce Lawsuit Against Trump Administration for Imposing Illegal Tariffs.

- 3. The Washington Post. Companies ready price hikes to offset Trump’s global tariff plans.

- 4. UBS. Raising U.S. taxes.

- 5. Cato Institute. Separating tariff facts from tariff fictions.

- 6. Peterson Institute for International Economics. Even now, tariffs are a tiny portion of U.S. government revenue.

- 7. Peterson Institute for International Economics. What populists don't understand about tariffs (but economists do).

- 8. Aspen Institute. Protectionism is failing and wrongheaded: an evaluation of the post-2017 shift toward trade wars and industrial policy.

Related articles