The Ultimate Guide to How to Trademark a Logo

Learn how to trademark a logo with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office — and how much it costs.

Many, or all, of the products featured on this page are from our advertising partners who compensate us when you take certain actions on our website or click to take an action on their website. However, this does not influence our evaluations. Our opinions are our own. Here is a list of our partners and here's how we make money.

If you’ve designed a logo for your business, you likely invested significant time and energy to create a distinct, recognizable and memorable symbol that visually represents the product and ethos of your company. That effort is worth protecting with a trademark.

To help you through this endeavor, this guide will break down how to trademark a logo with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office — as well as explain the levels of trademark protection and costs.

Benefits of trademarking your logo

If you’re unsure whether you want to trademark your logo, it’s important to understand that there are different types and levels of legal safeguards you can seek, and whether you go through the procedure yourself or outsource to a legal service for assistance, the most stringent protections will involve lengthy and costly processes.

If you opt for trademarking your logo, you’ll receive all of the benefits that come along with this designation, including:

- Authority to use your logo: By trademarking your logo, you’re legally establishing it as your own — meaning you’re the only one who can use the mark. If you find someone else using your logo, you then have the authority to stop them.

- Suing for trademark infringement: Once you’ve trademarked your logo, you can sue anyone who uses it without authorization and, if successful, receive compensation for any damages.

- Trademark outside of the U.S.: After you’ve trademarked your logo in the United States, you can then qualify to trademark your logo in other countries as well.

- Confiscation of goods: With a trademarked logo, you have the ability to stop the import of foreign goods that are infringing on your trademark.

- Building business identity: With a trademarked logo, you have taken a substantial step to solidify your business branding and with this base, you can continue to build and grow your business identity.

Levels of trademark protection

If you’ve decided that you’re ready to trademark your logo, there are a few additional considerations to take. First, you’ll want to think about the different levels of trademark protection and which you’ll want to get for your logo. The level of protection will not only dictate the cost, but also the specific steps you’ll need to follow regarding how to trademark a logo.

Local trademarks

Essentially, there are three levels of trademark protection — the first of which is a local trademark.

When you begin to use your logo in the course of everyday business activities, you are automatically entitled to certain regional protections under common law. Such rights vest the first time you utilize your logo in a commercial context. For example, the first time you displayed the logo on your website doesn’t qualify, but the moment you sold an item with your logo on it does.

You might have noticed items marked with a ™ (a trademark, which is used for goods) or ℠ (a service mark, which is used — just as you would imagine — for services), and these symbols suggest that someone asserts legal authority over that logo, slogan, etc.

These marks do not indicate, however, that any state or federal agency grants that authority, so these businesses are open to a breach of their intellectual property, in this case, trademark infringement, from anyone outside their local area. Only the coveted ® symbol shows that the recipient holds a federally registered trademark, which affords legal protection that will be explained shortly.

Therefore, the common law trademark option is the least costly but affords minimal protection. You’d likely win a lawsuit in your local jurisdiction against someone who copied your logo, but you might not have the same success outside of your region.

State trademarks

The next level of trademark protection is a state trademark.

If you plan to conduct business exclusively within one state, you might trademark your logo with that state. Typically, the secretary of state’s office where your business operates receives these trademark applications, and registration allows for the exclusive use of your logo within that state.

Although it’s a less expensive and far simpler process than a federal trademark petition, a state trademark once again limits your protections to a single geographical area and their extent will vary according to the laws of the state in question.

Federal trademarks

The final and most costly option is to trademark your logo on the federal level through the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). This guide will walk you through the basics of this process below, explaining how to trademark a logo with the USPTO.

Keep in mind, the USPTO process is extremely complex and time-consuming. Therefore, if you don’t want to invest time and effort to complete this process yourself, you might decide to acquire the assistance of an online legal service or trademark lawyer. These professional resources can help you through the process and ensure that you submit your application correctly as well as answer any related questions you may have.

Ultimately, despite the involved process required to trademark your logo with the USPTO, a federal trademark affords you the greatest legal protections. If the USPTO grants your application, it will place your logo on the Principal Register, which grants you:

- Legal ownership and exclusive use of your logo throughout the entire United States.

- The ability to file a business lawsuit in federal court against anyone who might infringe upon the above rights, and the capacity to collect appropriate damages from any winning claims.

- Authority to contact U.S. Customs and Border Protection and request that it confiscate any unauthorized imports with your logo on them.

- The right to register your trademark in other countries and to receive the full protection of their applicable laws.

- The use of the ® symbol beside your logo.

A federal trademark has its perks. Generally speaking, the larger your company, the more likely you are to both need and apply these protections.

How to get a logo trademarked with the USPTO

All of this being said, there’s nothing wrong with deciding to complete the federal trademark application yourself. Although the process is complex, it can be much more manageable if you take it one step at a time.

Step 1: Ensure your logo meets the necessary USPTO guidelines.

The first step involved with how to trademark a logo is ensuring that you’ll meet the qualifications necessary for the USPTO application.

Any item submitted for trademark must not already be in use by a previous applicant or be too similar to an existing trademark. You or your attorney can check at the federal level whether your logo is truly unique with a search of the trademark database on the USPTO’s website (shown below).

Source: USPTO

According to the USPTO website, one of the main reasons for the rejection of a trademark logo petition is “likelihood of confusion” with another company, which the agency explains as follows:

"One of the most common reasons for refusing registration is that a ‘likelihood of confusion’ exists between the mark in the application and a previously registered mark or a pending application with an earlier filing date owned by another party. Likelihood of confusion exists between trademarks when the marks are so similar and the goods and/or services for which they are used are so related that consumers would mistakenly believe they come from the same source."

This being said, not only does the USPTO attempt to avoid any mixups among logos and brands, but it also denies any applications whose contents it finds offensive. This may go without saying, but avoid obscenities or crude drawings.

The USPTO will also refuse any petition it finds misleading. For instance, if a logo — in the opinion of the USPTO — doesn’t clearly represent the type of product it claims to sell or is suggestive of another sort of item altogether, it will reject that application. You’ll want to remember that the USPTO exists to protect the rights of the business owner, but is also concerned about the consumer experience.

Step 2: Categorize your product.

Once you’ve determined that your logo complies with the USPTO requirements, the next step is to categorize your product. When you submit your trademark application, you’ll need to describe in detailed terms the good(s) or service(s) that your logo symbolizes.

The USPTO designates 45 different classes that your good or service may fall into — including, for example, a class that incorporates chemical products, another for cosmetics and another for machines and power-operated tools.

If you fail to appropriately classify your product using precisely the right words, the USPTO will deny your petition. Again, this is an area where parsing words is crucial and the advice of a legal trademark expert can prove invaluable.

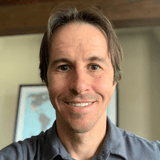

Step 3: Submit a “specimen” showing how your logo is used.

After you’ve decided which class or classes your product falls into, you’ll need to prepare a “specimen.” The USPTO requires a commercial example of your logo in use, called a “specimen,” in order to approve your application.

If your logo represents a physical product (as opposed to a service), an adequate specimen might include: photographs of your logo on the actual item you sell, a picture of the packaging or tags for your product that features your logo, or a photograph of a physical display in a store that sells your goods, where your logo is prominently featured.

Generally speaking, like the common law protections discussed above, your product specimen must demonstrate the use of your logo in the process of monetary exchange between you and your customer — not merely the usage of your logo on your own business materials.

Therefore, items like brochures, catalogs, press releases, business cards and other similar marketing materials typically won’t work as appropriate specimens in the goods category, as these don’t demonstrate a reciprocal relationship with your clientele.

If you are a service provider, however, the rules for a specimen are a bit more relaxed. Unlike for goods, materials used to advertise your company or in the course of daily business will suffice. Such items need only show a “direct association” between your logo and the services you offer and explain the nature of those services.

A sign, invoice, stationery or screenshots of a website where you offer your services are all acceptable specimens in this category, so long as the wording beside your logo clarifies the nature of your business.

You’ll need to submit a specimen for each type of good or service associated with your logo, if there’s more than one, and pay the appropriate fees for each.

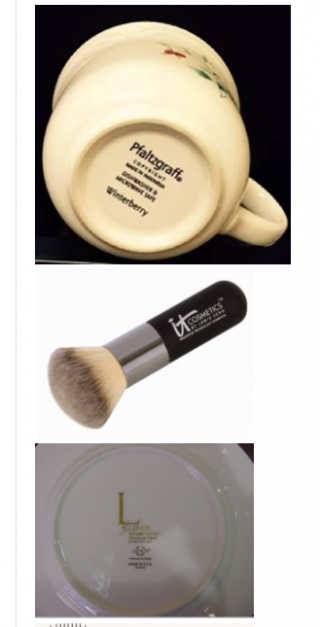

Step 4: Wait for a reply from the USPTO.

At this point, you’ve completed the main pieces necessary to file your trademark application. Once you’ve done so, you should receive a confirmation from the USPTO right away. After that, though, it’s likely to be several months before you receive further communication from the agency. In fact, the entire application process can take six months to one year, and sometimes longer — if any issues arise that require resolution.

In the meantime, you can check the status of your application in the Trademark Status and Document Retrieval database. You can use the serial number provided on your initial receipt to retrieve information about your petition. You can also check the current average processing times for applications.

You may be wondering why it takes so long to process a trademark application. Here’s what’s happening behind the scenes:

- First, the USPTO reviews your application to ensure that you have met the basic filing requirements. If you haven’t, the agency will notify you.

- Next, the USPTO sends your petition to an examining attorney. It can take several months for your application to arrive on their desk.

- The examining attorney scrutinizes every element of your application. Their job is to establish whether you’ve met all the legal and procedural hurdles of a viable petition. The attorney will double-check for redundant trademarks (as explained in step one above), decide whether you’ve properly classified your product, ascertain whether you’ve submitted an appropriate specimen and ensure that you’ve included the proper fees.

It is solely at the discretion of the examining attorney whether your logo will be registered. If not, the attorney will contact you. If the issues with your application are minor, you may receive a call or email. If the concerns are more involved, you will receive a letter called an Office Action that outlines the reasons for the denial.

Step 5: Correct application errors, if any.

If the USPTO rejects your application based on an administrative or regulatory issue that you can resolve, you’ll have the opportunity to correct the problem. If the agency refused your petition because of an inherent flaw in your logo or similarity to an existing trademark or application, you’ll have to go back to the drawing board and start the process over again.

If you receive an Office Action, you will have six months from the date of mailing to submit the requested corrections, or the USPTO will mark your application as abandoned. If your submission does not satisfy the examining attorney, you'll be issued a final refusal of your application. You can appeal this denial to the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB), an administrative court with the USPTO, if you desire. This being said, however, such an appeal will incur additional fees.

On the other hand, should the examining attorney approve your application, your logo will be published in the Official Gazette. This regulation is a holdover from pre-internet days, and theoretically puts the public on notice that your logo is soon to be a registered trademark. If anyone believes they might be harmed by this registration, they have 30 days to file their grievances with the USPTO.

If no one files, (and unless you’re a Fortune 500 company, it’s unlike that anyone will) your logo officially becomes a federally registered trademark — with all the rights and protections discussed above.

Step 6: Maintain your trademark rights.

At this point, you now know how to trademark a logo — however, once you hold a registered trademark, there are other actions you’ll need to take.

First, to maintain your protected status, you’ll need to submit a Trademark Declaration of Continued Use and a Trademark Renewal to the USPTO every five years. If you neglect to file this renewal, you’ll have a six-month grace period in which you can still file — this will cost additional fees, however.

If you fail to submit these forms entirely, though, the USPTO will consider your logo abandoned and you will lose all of your legal intellectual property protections.

Therefore, you don’t want to let your registration renewal slip through the cracks. You’ll also want to remember that there’s no limit to the number of times you can renew your trademark, as long as your logo remains in commercial use.

Step 7: Enforce your protections against infringement.

Finally, to ensure that no other business uses their logo improperly or without their permission, many companies engage in what’s called a trademark watch. This process requires constant vigilance to guard against the misuse of your logo and to potential applications to the USPTO for comparable logos. The larger your company, the more you may need this type of service.

Usually, a business will hire a legal firm or other specialized company to engage in a trademark watch. These representatives will send cease-and-desist letters if they do encounter a logo that’s similar to yours, and will also engage in litigation to enforce your intellectual property, protecting the sanctity of your logo, if necessary.

If you’re a smaller business, this step may not be necessary — nevertheless, it’s always a good idea to keep an eye out for trademark infringement and assert your rights under trademark protection if you do find an infringement.

How much does it cost to trademark a logo?

At this point, you might be wondering: How much does it cost to trademark a logo?

Ultimately, the cost of the process will depend on which level of trademark protection you decide you need for your logo. If you opt for local protection, simply using your logo in your immediate area, you won’t have to pay for an actual trademark application, however, this level affords you very limited protection on your intellectual property. Even if you use the ™ symbol, this doesn’t indicate authorization from any state or federal authority, and therefore, you’re more open to trademark infringement from other businesses.

If you decide to apply for a trademark for your logo within your state, however, you will receive official legal protections from the state, but this will come with an associated cost. The exact cost will depend on the specific state — but by consulting the official website in your state, you can find out the details about both cost and process. Trademark pricing ranges, from $30 in Alabama, for example, to $50 in New York and $70 in California.

Nevertheless, whatever the cost in your specific state, it will most definitely be cheaper than the cost to register for a trademark with the USPTO. In fact, the USPTO breaks down the variety of fees that may apply to your trademark application, explaining that, “almost all trademark fees for any part of the process are calculated on a ‘per class basis’ for all listed goods or services, which will make overall fees higher if goods or services fall in more than one class.”

This being said, however, there are two options for the initial application fee for electronic filing of a trademark application with the USPTO:

- TEAS Plus: $250.

- TEAS Standard: $350.

Although these are the standard fees for a USPTO trademark application, there are other factors that may contribute to the final cost, including the number of classes, the option selected, method of filing (online vs. paper) and fulfillment of requirements.

If, for example, you apply for a trademark for your logo and need to make a correction to the application, this will cost an additional $100 per class. Similarly, you’ll be charged $100 simply for the USPTO to issue a new registration certificate.

Because of the high cost of a federal trademark application, as well as the variety of fees you may face, it’s all the more important to be sure that you’re ready to trademark your logo, and if you are, that you complete the application fully and accurately.

For this reason, many business owners choose to work with a trademark lawyer or legal service. A trademark lawyer, however, will likely be even more costly, as they can charge anywhere from $1,000 to $2,000 for the full application process, in addition to your filing fees.

Trademarks vs. copyrights and patents: What’s the difference?

Now that you understand how to trademark a logo, you might be curious about the other types of legal protections. In addition to a trademark, copyrights and patents also protect intellectual property.

In short, the difference between these three types of protection comes down to the type of material that you’re trying to legally safeguard against unauthorized use.

Trademarks protect a “mark” of a “trade” — things like company names, slogans or logos. Copyrights, on the other hand, protect the creative content of your business — such as a movie, song or manuscript. Finally, patents protect inventions — either the intricacies of how something works or conversely, how something looks.

A version of this article was first published on Fundera, a subsidiary of NerdWallet

Article sources

NerdWallet writers are subject matter authorities who use primary,

trustworthy sources to inform their work, including peer-reviewed

studies, government websites, academic research and interviews with

industry experts. All content is fact-checked for accuracy, timeliness

and relevance. You can learn more about NerdWallet's high

standards for journalism by reading our

editorial guidelines.

More like this

Related articles